Providing Health Information to a Science-Resistant Audience

With each passing news cycle, the presence of misinformation and public skepticism (or outright rejection) of scientific advice reminds me of the challenges in health-related communications. The partisan divide on coronavirus mask mandates in the United States is one example of how expert health recommendations can fail to land with segments of the American public.

As a health organization, you likely provide some degree of science-backed information to your constituents as part of your work. Have you considered how misinformation and public trust in science impacts the effectiveness of your communications?

Data indicates most Americans haven’t stopped trusting science (but they don’t always believe its findings)

First, some important context:

- Way back in 2015, The Atlantic reported that most Americans are positive about science’s impact on the quality of health care, food, and the environment.

- However, just because Americans trust science does not mean they believe its findings. The Atlantic notes that “facts often have little bearing on how someone feels. That climate change is real (and caused by humans), and that vaccines are safe, are two of the most evidence-heavy, backed-up statements we have in modern science. Whether people believe them may have nothing to do with whether they trust scientists or not.“

- In May 2020, a FiveThirtyEight survey found—contrary to what you might expect —” [t]he scientific and medical communities remain among the most trusted institutions in America — even among people who might seem ideologically primed to reject them.”

- However, a recent Pew study noted that “trust in practitioners like medical doctors and dietitians is stronger than that for researchers in these fields, but skepticism about scientific integrity is widespread…respondents expressed less trust in scientists to report findings that disagree with the interests of the research sponsor.”

The findings show a fascinating duality. Americans may trust the scientific process, but they don’t always agree with the conclusions it brings. Part of that skepticism is due to perceived conflicts of interest with the research sponsor. There’s more to it, however.

Attitudes toward science vary based on the issue

Despite what you might think from reading the news, data indicates there is no such thing as a single anti-science population.

An enlightening report published in 2018 by the American Academy of Arts & Sciences (The Academy) found that “[a]ttitudes toward science are not uniformly associated with one particular demographic group but instead vary based on the specific science issue. […] These data make clear that no single monolithic ‘public’ exists when considering views on scientists and scientific issues.”

For health organizations, this highlights the importance of understanding and researching your audience. Characteristics such as age, race, educational attainment, region, and political ideology can impact someone’s confidence in science. The first step is to understand who is engaging with your organization to communicate with them effectively.

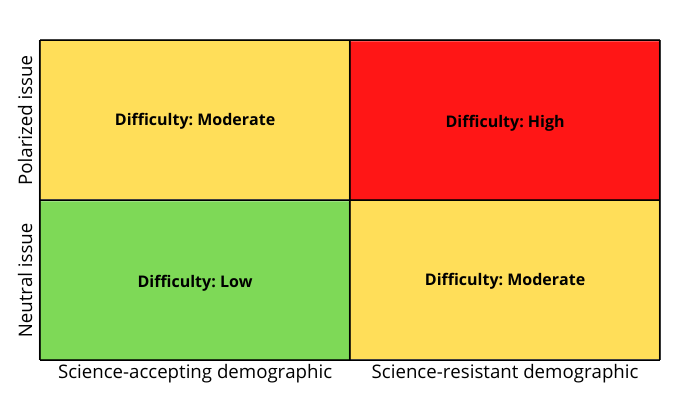

Because attitudes toward science depend on the issue, be aware of the difficulty of each topic your organization communicates around. The combination of issue + demographic will determine the level of challenge you face:

Many people also struggle to distinguish fact from opinion in the news. This struggle can influence their perception of the issues your organization addresses. Clarifying the facts for your audience may help people identify where they have allowed an opinion to influence their view of a particular health issue.

People feel science is changing their way of life too fast

Digging deeper into the data, The Academy found that while people are aware of the benefits of research, the majority of Americans (52%) believe that science makes their way of life change too fast.

“For the approximately 10 percent of Americans who did not complete high school, the vast majority (69 percent) agreed that science makes life change too fast. In comparison, 36 percent of those with a bachelor’s degree expressed this sentiment […] respondents with lower family income also were more likely to agree with the statement.”

Simply put, if the science-backed information you’re providing threatens to change someone’s way of life, you are likely to encounter resistance. If that person is also part of a science-resistant demographic, you may face outright denial.

There is no magic bullet here. However, behavioral change models provide clues to how to structure your communications to give them a better chance of landing.

For example, the Transtheoretical Model highlights several processes by which people progress through stages of change. Understanding these processes may help you present your information in a different light to break through a change-resistant barrier.

To cherry-pick a few underused ones:

- “Dramatic Relief – Emotional arousal about the health behavior, whether positive or negative arousal.”

- “Self-Reevaluation – Self reappraisal to realize the healthy behavior is part of who they want to be.”

- “Social Liberation – Environmental opportunities that exist to show society is supportive of the healthy behavior.”

- “Helping Relationships – Finding supportive relationships that encourage the desired change.”

These processes go beyond simple awareness-raising and fact-presenting to address deeper resistances to change. Coupling this with user research and journey mapping gives you a more powerful toolkit to deliver the right information, in the right way, at the right time, to each segment of your audience.

Key takeaways

Health information in today’s landscape is a complex problem. Keep in mind:

- Trust in the scientific process is high, but people don’t always agree with researchers and experts’ conclusions.

- Resistance to science is determined by a combination of your specific health issue and audience demographics, underpinned by the threat of change to their way of life.

- A deeper understanding of your audience, coupled with the use of behavioral change models, can help you get your information across more effectively.

Unfortunately, the challenges we face in health communications will likely not disappear anytime soon. However, the good news is that we have the tools to begin taking action on this problem now—and improving health outcomes as a result.